This is the second in a five-part series about the final status issues in the Israel-Palestinian conflict

If you follow the headlines, you may think the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians is mostly about land or refugees. But there is another word that comes up over and over: Jerusalem.

For Jews and Israelis, Jerusalem is the capital: not just politically, but historically and spiritually. For Palestinians, East Jerusalem is the city they want as the capital of their own future state. And layered on top of both claims are the religious dimensions: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim holy sites clustered within a single square kilometre of the Old City.

That is why Jerusalem has always been one of the five “final status” issues reserved for negotiation, and why it has repeatedly made or broken peace talks. To quote the fictional Israeli Prime Minister Zahavy from The West Wing, “My right eye will fall out, my right arm will fall off, before I ever sign a document giving up Jerusalem!”

There has never been any consensus about Jerusalem.

Oslo: Deferred to Final Status

The Oslo Accords of the 1990s deliberately set Jerusalem aside. Both sides knew it was the most sensitive issue. Instead, they agreed to address it later, along with refugees, security, borders, and settlements. The idea was that confidence could be built on easier issues before tackling the hardest one.

In practice, that meant that when leaders finally sat down to discuss Jerusalem directly, they were already burdened with decades of mistrust.

Camp David 2000

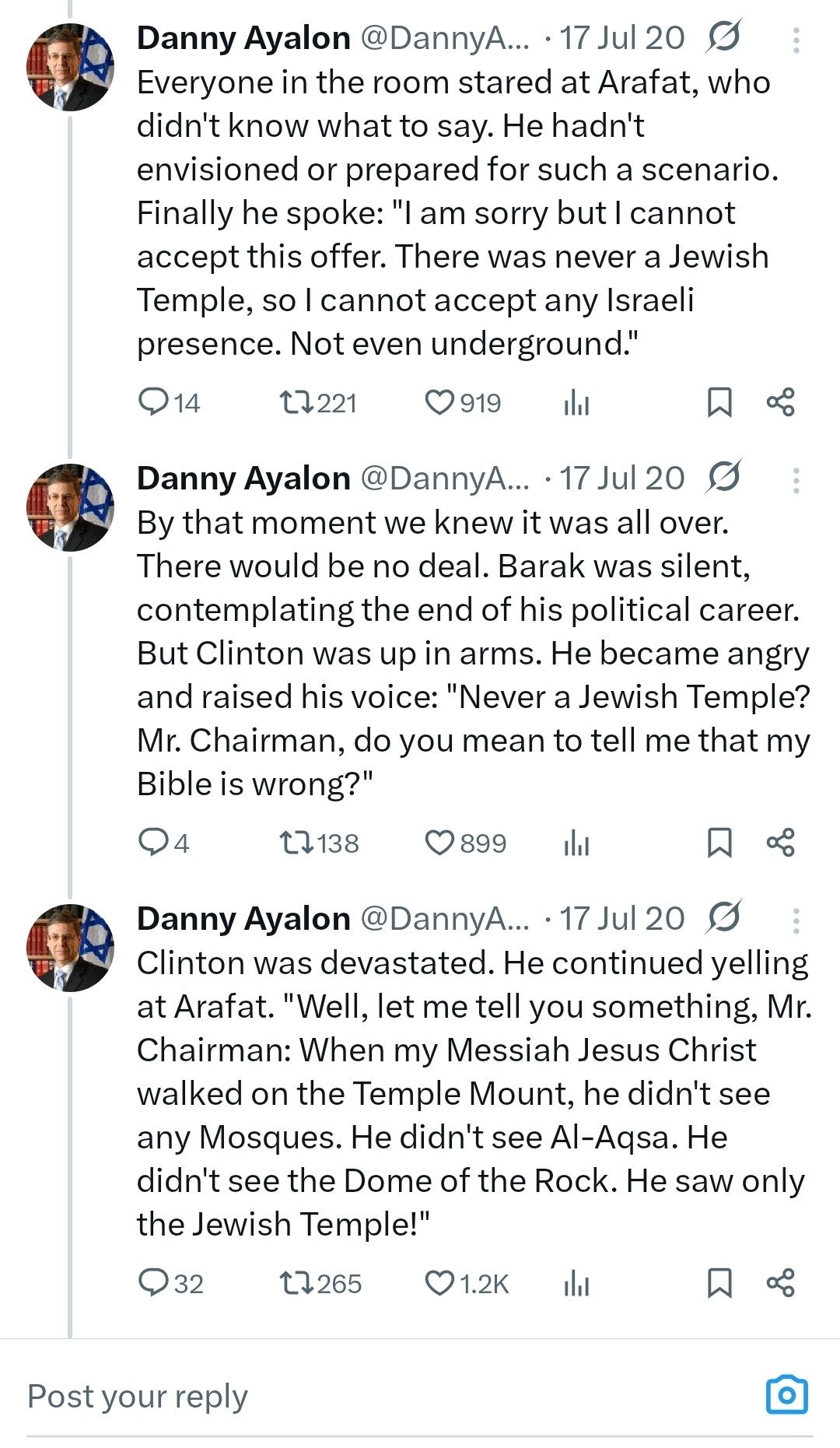

At Camp David in July 2000, President Bill Clinton brought Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and Palestinian Authority President Yasser Arafat together to attempt a final deal.

For the first time, an Israeli leader put Jerusalem on the table. Barak suggested that Arab neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem could come under Palestinian control, while Israel would keep Jewish neighbourhoods. The Old City and especially the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, however, proved impossible.

Israel insisted on sovereignty or at least security control over the Temple Mount, unequivocally Judaism’s holiest site. Arafat rejected any compromise that did not give the Palestinians sovereignty there, even foolishly denying that a Jewish Temple ever stood on the site, a claim that flew in the face of archaeology, history, and common sense. The talks collapsed.

The Clinton Parameters

After Camp David failed, Clinton proposed bridging ideas in December 2000. His parameters suggested:

Jewish neighbourhoods in Jerusalem would be under Israeli sovereignty.

Arab neighbourhoods would be under Palestinian sovereignty.

Israel would retain the Western Wall.

The Palestinians would hold sovereignty over the Temple Mount, with special arrangements for archaeology and excavation.

This was a radical shift: the US explicitly proposing shared sovereignty in Jerusalem. Israel said it was a serious basis for negotiation. The Palestinians, still unwilling to concede any Jewish rights on the Temple Mount, hesitated and ultimately walked away.

Taba 2001

In January 2001, negotiators met again in Taba, Egypt. Building on the Clinton Parameters, they discussed detailed arrangements for the Old City. The idea of a special regime in the Holy Basin - i.e. the Old City and its immediate surroundings -was floated, possibly involving international participation.

Once again, elections in Israel cut the talks short. Ariel Sharon came to power, and the Taba suggestions were shelved.

Annapolis 2008: Olmert’s International Proposal

In 2008, Prime Minister Ehud Olmert put forward what may have been Israel’s boldest proposal on Jerusalem. He suggested that the Holy Basin, including the Temple Mount and surrounding holy sites, be placed under a five-member international trusteeship: Israel, the Palestinians, Jordan, the United States, and Saudi Arabia.

This would mean no one party had full sovereignty, but all had a say in administration and access. Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas did not accept the offer, pushing for Palestinian authority over the neighbourhood of Silwan, which Olmert said should fall under international control. Again, the talks ended without agreement. Once again, Israel had shown flexibility and a willingness to negotiation, whereas the Palestinians walked away.

Why Jerusalem Is So Difficult

Jerusalem is not just a political capital. It is a city of symbolic weight. For Jews, it has been the centre of prayer and longing for thousands of years: we face Jerusalem to pray, we end our Passover seders declaring “Next year in Jerusalem,” and the city is mentioned 667 times in the Torah. For Muslims, the Haram al-Sharif (Temple Mount) is the third holiest site in Islam (after Mecca and Medina), though Jerusalem is not mentioned once in the Quran. For Christians, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is one of the most sacred sites in the world, said to be the location of Jesus’s crucifixion and entombment.

This means that any compromise feels existential. Israelis fear losing secure access to the Western Wall and other Jewish holy sites. Palestinians fear being denied their claim to East Jerusalem and the Haram which includes the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque. Both worry about how sovereignty and security interact in such a small, sensitive space.

Israel’s Position on Jerusalem

Israel’s stance has evolved, but certain principles have remained consistent:

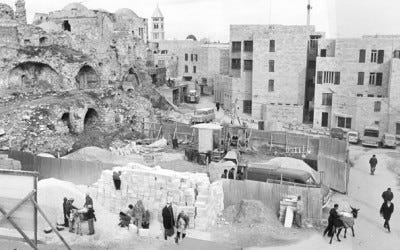

Jerusalem is Israel’s capital. In December 1949, Prime Minister Ben Gurion declared that Jerusalem was Israel’s capital city. Since 1967, when the Old City and East Jerusalem was taken back from Jordan, Israel has insisted that the entirety of Jerusalem remain united under its sovereignty. Over the years, negotiators have shown openness to functional divisions, but not to re-dividing the city with barbed wire, checkpoints, and violence as it was between 1948 and 1967.

Access to holy sites must be guaranteed. Israel points to its record since 1967 of keeping access open for all religions, compared to the Jordanian period (1948–1967) when Jews were barred from the Old City and the Jewish Quarter and its synagogues were all destroyed. Under Israel, Christians, Muslims, and Jews have all had access to their holy sites.

Security control is essential. No arrangement can put the Old City or the Temple Mount beyond Israel’s ability to prevent violence or terror. Repeated riots, stabbings, and incitement show what happens when extremists are given free rein.

Arab neighbourhoods could be administered separately. In negotiations, Israel has shown willingness for Arab areas in East Jerusalem to be under Palestinian civic or even sovereign authority, provided Israel retains some security oversight given the proximity to Israeli territory/populations.

The Palestinian Position on Jerusalem

The Palestinians insist that East Jerusalem, including the Old City, must be the capital of their state. They view this as a matter of national identity and international law, since most of the world never recognized Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem after 1967. On the other hand, Ramallah as a Palestinian city (and effectively the Palestinian capital city today, makes far more practical sense).

On the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount, Palestinians demand full sovereignty. They have sometimes been open to Jordanian custodianship, but they reject any permanent Israeli role. Meanwhile, Palestinian leaders (and now, surprise surprise, the UN) often deny Jewish historical ties to Jerusalem altogether, erasing 3,000 years of Jewish history. This is a ridiculous posture that makes compromise harder, not easier.

Conclusion

Jerusalem illustrates why “recognition” alone cannot resolve the conflict. You can declare a Palestinian state tomorrow, but unless you resolve how sovereignty, administration, and security work in Jerusalem, you will be left with competing claims to the same city. Ask Prime Minister Carney: “What is the capital city of the Palestinian state you just recognized?” There is no clear answer at this time.

For Israel, Jerusalem cannot be divided in a way that endangers security or cuts Jews off from their holiest sites. It is the eternal capital of the Jewish people, where Israel has already demonstrated its ability to protect the rights of all faiths. For Palestinians, they may allege that a state without East Jerusalem as its capital feels hollow and illegitimate, but their repeated rejection of workable compromises has kept peace out of reach.

This is why Jerusalem remains one of the most intractable unresolved final status issues. Until a workable compromise is reached, one that recognizes Israel’s historic rights, its security needs, and its proven record of safeguarding holy places, any shortcut to statehood risks building more frustration instead of peace.

Tomorrow we deal with the issue of Borders.

Well, let’s see.

What were the rights of Jews when the Old City was under Arab control?

And what have been the rights of Arabs since it has been under Jewish control?

‘Nuff said. It really is that simple.

Unfortunately there is an answer to the question “what is the capital of the state you just recognized” - the New York Declaration recognizes the 1969 borders.