This is the third in a five-part series about the final status issues in the Israel-Palestinian conflict

“Two states for two peoples.” It sounds simple: draw a line, shake hands, and live side by side. But in practice, drawing that line has been one of the thorniest issues in every Israeli–Palestinian negotiation.

Borders aren’t just about maps. They dictate who controls scarce water resources, who secures the Jordan Valley, which roads are safe, whether Israel remains defensible, where this or that olive grove belongs, and whether a Palestinian state would actually function. They are the difference between peace on paper and chaos on the ground. Just ask the British Colonial Regime.

Oslo: Kicking Borders Down the Road

Like with security guarantees and Jerusalem, the Oslo Accords of the 1990s avoided the question of final borders almost entirely. Instead, they divided the West Bank into Areas A, B, and C:

Area A: full control by the Palestinian Authority (PA),

Area B: civil control by the PA with joint security controil between Israel and the PA,

Area C: under Israeli military control.

This was never meant to be permanent. Final borders were left for later. But like each other issue, that “later” has dragged on for three decades.

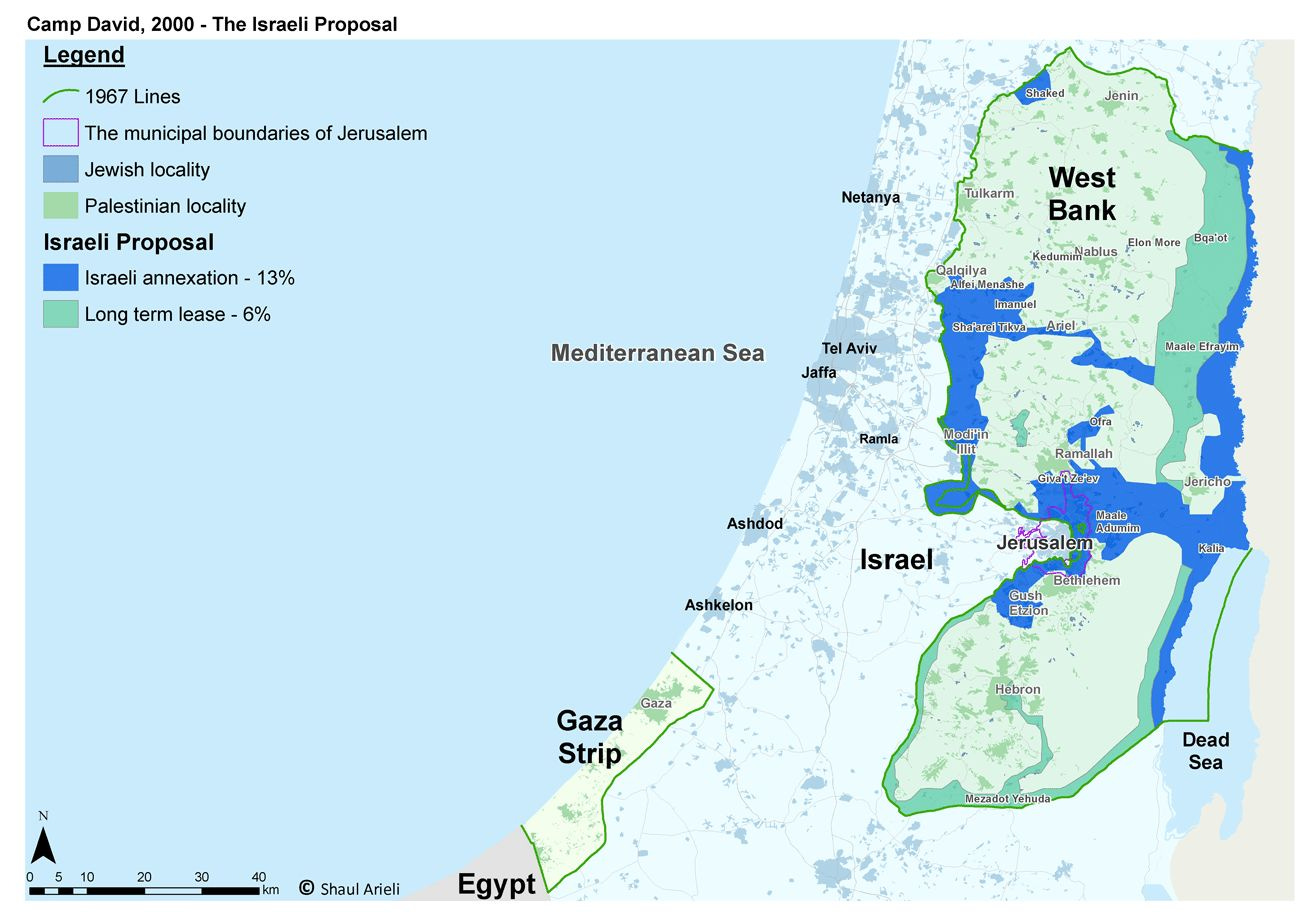

Camp David 2000: First Attempt at a Map

At Camp David in 2000, borders were put on the table. Prime Minister Ehud Barak proposed annexing the large settlement blocs, those areas just beyond the 1967 “Green Line” where hundreds of thousands of Israelis live, many in suburbs of Jerusalem. This is what is typically referred to as the “Etzion Bloc.”

For Palestinians, this seemed to be a way to cut off Jerusalem and take more of the West Bank that the Israelis were allegedly not entitled to (despite the fact that the West Bank or ‘Judea and Samaria’ is Biblical Israel). They demanded a full return to the 1967 lines (i.e. the entirety of the West Bank) with only token land swaps. As the history goes, instead of countering, Arafat walked away, giving the go-order for the Second Intifada, with suicide bombings and terror attacks that shredded what little trust Oslo had built.

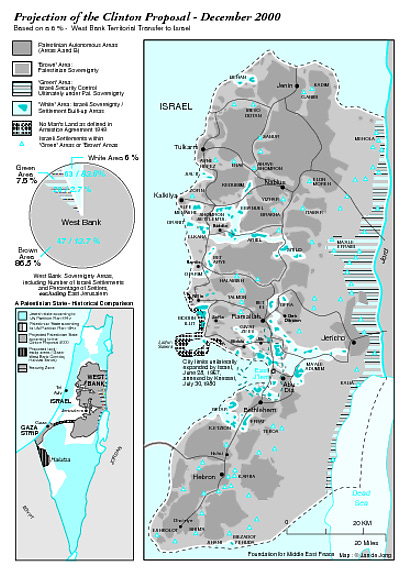

The Clinton Parameters: Land Swaps Enter the Game

In December 2000, Bill Clinton proposed a compromise:

Israel would annex 4–6% of the West Bank, including major settlement blocs,

The Palestinians would get 1–3% of land inside Israel in exchange,

The end result: a Palestinian state on 94–96% of the West Bank.

Israel was willing to negotiate on this basis. The Palestinians hesitated, then rejected it. Again, no counter-offer.

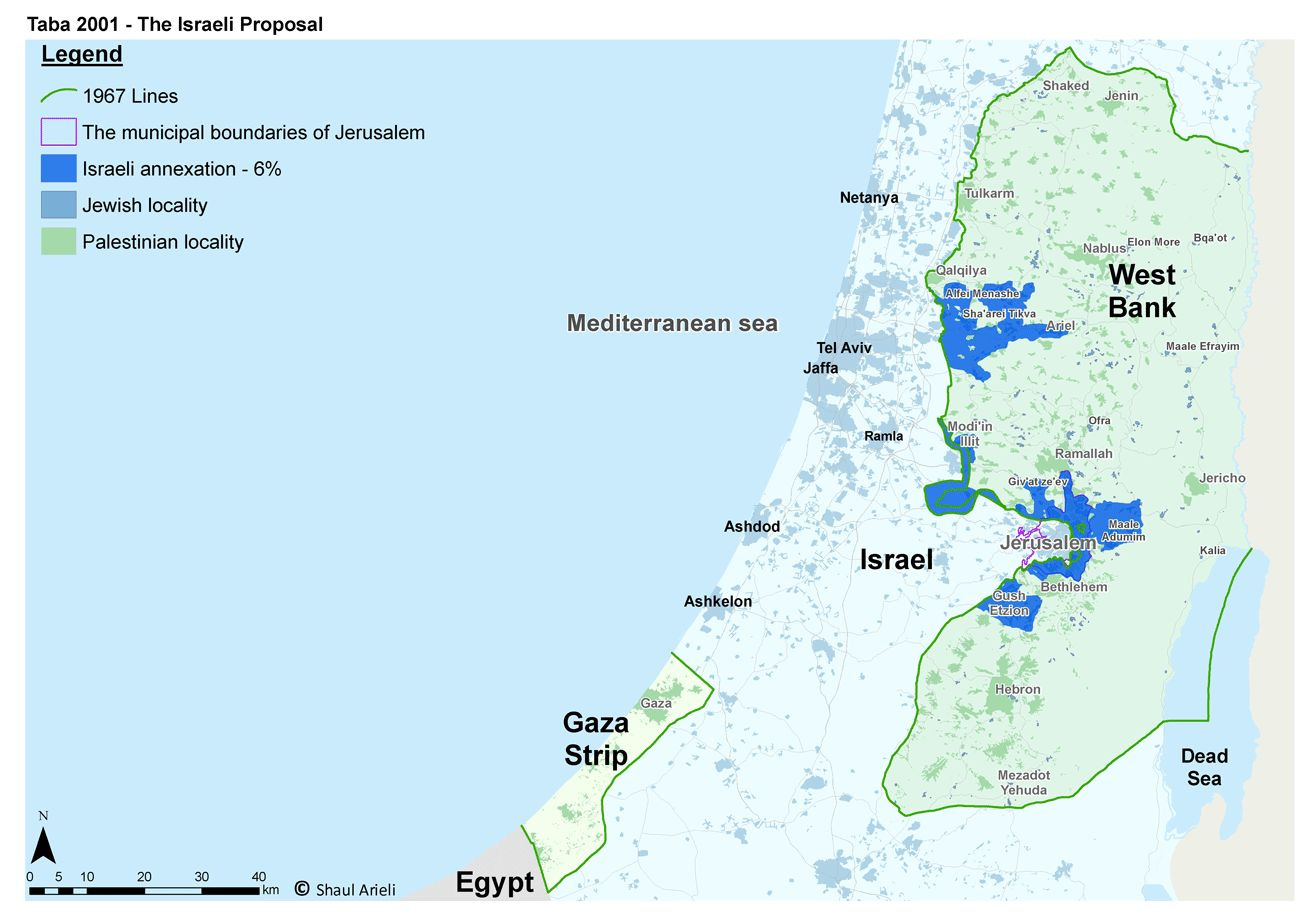

Taba 2001: Closing In

Talks at Taba in January 2001 brought the sides closer than before. Israel reduced annexation demands to around 3%. The Palestinians hesitated. But as Israeli elections loomed, the talks ended. Ariel Sharon took over the Premiership from Ehud Barak, and any momentum was lost.

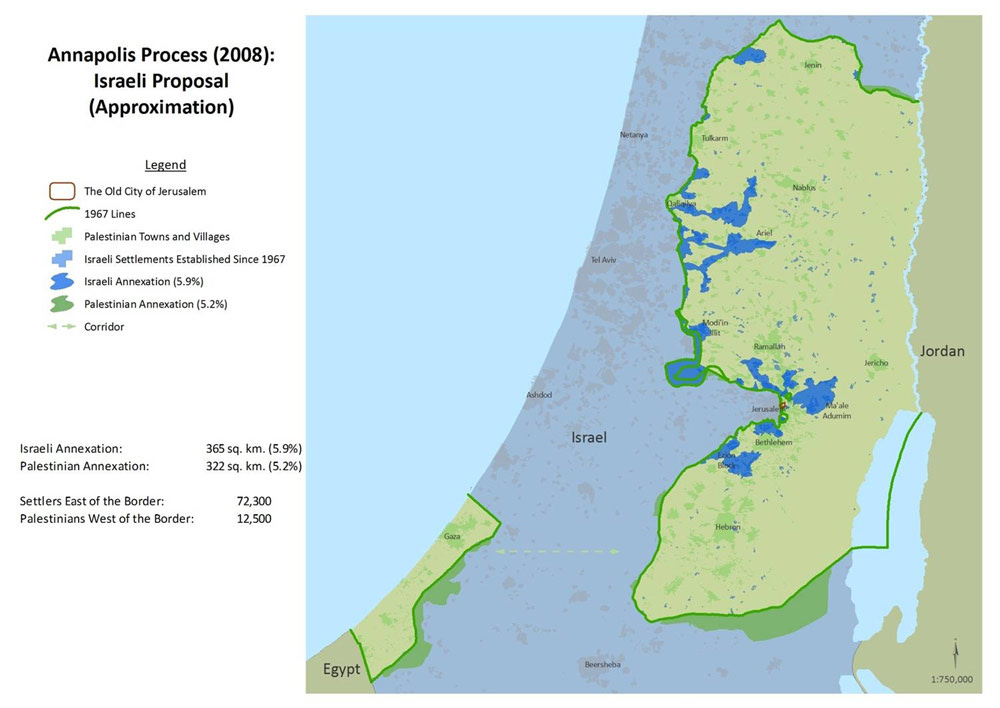

Annapolis 2008: Olmert’s Detailed Map

In 2008, now three years after Israel had unilaterally disengaged from Gaza, and one year after Hamas ousted Fatah from Gaza in a bloody coup, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert presented the PA’s Mahmoud Abbas with the most detailed Israeli offer yet:

Israel would annex 6.5% of the West Bank, covering the settlement blocs,

Palestinians would get 5.8% of Israeli land in exchange, plus a corridor linking Gaza to the West Bank,

87% of settlers would remain inside Israel under this plan.

Abbas admitted later that Olmert’s map was “serious”, but of course refused to negotiate or counter. Once again, no counter-map, no alternative vision, just Palestinian rejection. Even when presented with 94% of the land, a capital in East Jerusalem, and international involvement in holy sites, Abbas chose to stall rather than compromise. The power of the Palestinian cause is their being stuck in limbo, which gets lost if they agree to something, so they demur. Rinse, repeat.

Why Borders Are So Difficult

Settlements. More than 600,000 Israelis live beyond the Green Line. You cannot simply uproot entire cities like Ma’ale Adumim or neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem and pretend they don’t exist.

Security. At its narrowest point, Israel is just nine miles wide. Surrendering strategic terrain without safeguards is an open invitation to have rockets fired on Ben Gurion Airport.

Contiguity. Palestinians want a state that isn’t a checkerboard. Too much annexation risks breaking continuity. But Israel cannot accept a “contiguous Palestine” if it means an indefensible Israel.

Israel’s Position on Borders

Israel’s negotiating red lines have been largely consistent, though what they have been willing to hand over has changed:

1967 lines are indefensible. The historic “Green Line” (called such because they were drawn on a map with a green pencil) were armistice lines, not intended to be international borders, and left Israel vulnerable on several fronts.

Settlement blocs must remain. Communities housing hundreds of thousands of Israelis, many considered suburbs of Jerusalem, are not going anywhere. There is no sense in uprooting all those people and those cities when land swaps on more valuable and arable land were once considered/proposed.

Land swaps are possible. Israel was, at one point, willing to trade land inside pre-1967 territory to balance annexation.

Jordan Valley control is essential. Israel insists on a long-term security presence along the eastern border to prevent weapons smuggling and infiltration.

Israel made offers again and again, each more generous than the last. The common thread? Palestinians say no, pocket the concession, and then demand more next time. Terror continued unabated.

The Palestinian Pattern of Rejection

This is not just about one deal falling through. It is a pattern. As Israel’s Foreign Minister Abba Eban infamously said, “The Palestinians never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity”:

1937: Peel Partition: The Jewish population accepted a tiny state, while the Arabs rejected a larger Arab state, because it would mean the establishment of a Jewish state.

1947: The UN Partition Plan: Jews accepted a small state, Palestinians rejected any state as long as a Jewish state existed, and launched a war. Israel won.

2000: Camp David: Israel offered unprecedented concessions, Palestinians said no, and launched the bloody Second Intifada.

2008: Olmert’s offer: the most generous Israeli offer in history, which Abbas also rejected, walking away with no counter-offer.

At each juncture, Israel demonstrated flexibility, while Palestinian leaders chose rejection over compromise. That record matters. It shows why recognition of a Palestinian state now - without negotiated borders - only rewards decades of saying “no.”

The Blindness of Western Recognition

This is what makes the recent rush by Western governments to “recognize Palestine” so bananas. Leaders in Ottawa, London, Paris, and Canberra act as if they are unlocking the door to peace, when in reality they are slamming it shut. By ignoring the history of Palestinian rejectionism, not just by Hamas but by Fatah too, they signal that refusing every compromise and clinging to maximalist demands - not even waiting for the hostages to be released! - will eventually be rewarded. It is the diplomatic equivalent of giving a prize for bad behaviour.

When France or Canada declares that Palestine is a state without defined borders, without a peace agreement, and without any functioning unity between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, they are not advancing peace but erasing the very principle of negotiation. It is virtue signalling for their home-base, which has no material impact on peace in the Middle East. Ask President Macron or Prime Minister Starmer what the borders of Palestine are today. This is not a question they can possibly answer, as no one would give the same response. Every previous peace framework, from Oslo onward, was built on the idea that borders must be mutually agreed. In fact, the Oslo Accords even said that the Palestinians could not unilaterally declare a state without agreement on these final issues, but that’s all in the rear-view mirror at the moment. To declare borders largely irrelevant now is to abandon the only path that has ever had a chance of producing a lasting settlement.

Conclusion

The question of borders embodies the deepest questions of survival. For Israel, borders must mean security and keeping large, established communities within its sovereignty. Though it sounds childishly simple, one of the most important questions in geography is: Where is it? Tell me the answer when it comes to Palestine. I’ll wait.

Still waiting.

History shows that Israel has repeatedly offered maps, percentages, and swaps, while Palestinians have repeatedly walked away, usually with violence in tow. Western governments now rewarding that history with meaningless and symbolic recognition only entrenches rejectionism.

Until the question of borders is resolved in a way that ensures Israel’s security and reflects on-the-ground realities, talk of “recognition” will remain an empty gesture or worse, a gesture that makes real peace less likely.

Tomorrow, we will discuss the issue of Refugees.