The history

Many do not know the history of the Israeli anthem, Hatikvah: The Hope.

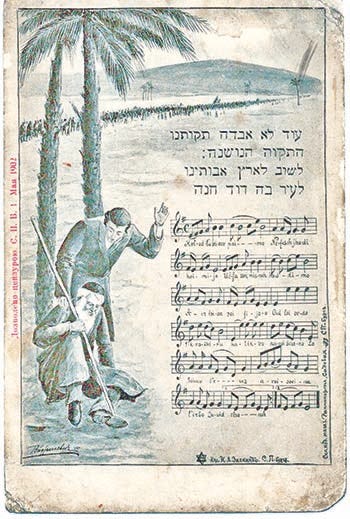

It was first published in 1878, written by an obscure (and usually drunk) poet named Naftali Herz Imber. Galician by birth, when he was 22 years he was staying with a Talmudist in Romania, when he wrote a poem then called Tikvatenu: Our Hope.

The original poem was nine stanzas:

Our hope is not yet lost,

The ancient hope,

To return to the land of our fathers;

The city where David encamped.As long as in his heart within,

A soul of a Jew still yearns,

And onwards towards the ends of the east,

His eye still looks towards Zion.As long as tears from our eyes

Flow like benevolent rain,

And throngs of our countrymen

Still pay homage at the graves of our fathers.As long as our precious Wall

Appears before our eyes,

And over the destruction of our Temple

An eye still wells up with tears.As long as the waters of the Jordan

In fullness swell its banks,

And down to the Sea of Galilee

With tumultuous noise fall.As long as on the barren highways

The humbled city-gates mark,

And among the ruins of Jerusalem

A daughter of Zion still cries.As long as pure tears

Flow from the eye of a daughter of my nation

And to mourn for Zion at the watch of night

She still rises in the middle of the nights.As long as the feeling of love of nation

Throbs in the heart of a Jew,

We can still hope even today

That a wrathful God may have mercy on us.Hear, oh my brothers in the lands of exile,

The voice of one of our visionaries,

[Who declares] that only with the very last Jew,

Only there is the end of our hope!

Not a happy song, necessarily, it speaks of never losing hope in the midst of a tragic history marked by tears.

A few years later, an early Zionist named Shmuel Cohen set the poem to music. The melody (often described as “I’m a little teapot” in a minor key), goes back 600 years to a Sephardi prayer for dew, Birkat Ha’tal. The melody found its way to Italy, and became a popular love song called “Fugi, Amore Mio” (Flee, flee, my love!). It then evolved into a Romanian gypsy folk song called “Cart and Oxen”, before 17 year old Cohen used the tune to make “Hatikvah”, the song we know today:

As long as in the heart, within,

The Jewish soul yearns,

And towards the ends of the east,

[The Jewish] eye gazes toward Zion,

Our hope is not yet lost,

The hope of two thousand years,

To be a free nation in our own land,

The land of Zion and Jerusalem.

The song’s popularity grew. It permeated Jewish culture. Famously, it was sung by partisans fighting the Nazis in forests, and Jews seeking mercy, imprisoned in death camps. A famous recording has survivors singing it outside the liberated Bergen Belsen Camp in 1945. It still brings me to tears every time I hear it.

In 1948, Hatikvah became the de facto anthem of the State of Israel, interestingly, one of the only national anthems in the world in a minor key. It stands in stark contrast on the world stage to the military marches of so many other anthems. Only on November 10, 2004, was Hatikvah officially adopted as Israel's anthem, in the Flag, Coat of Arms, and National Anthem Law.

Theodor Herzl, notably, detested Hatikvah. This is probably because he knew Imber was a drunk, and wanted something more uplifting. He organized a contest for a new anthem in 1903, but Hatikvah stuck. It was sung as a rallying cry at the Sixth Zionist Congress by those who opposed the Uganda Plan (seeking a potential Jewish State in East Africa), and who insisted that it was Eretz Yisrael or nothing, as a future Jewish State.

Hatikvah, is also a source of dispute in Israel today. Many believe it is inappropriate as a national anthem because it mentions the Jewish soul, when there are many non-Jews in Israel. The anthem is about Jews abroad, not the State of Israel itself, and there have been efforts to edit the anthem to make it more inclusive, to no avail.

Israel Samuels, a reader in Rabbinics at Cambridge University, once wrote that,

Hatikvah owes its fame to its directness of sentiment, and the power of Hatikvah arises from its directness. There is no subtlety in its thought, no changes through its nine verses. The hope of a return to the Land of Israel will never die so long as this or that endures.

Hope

And that's what I’m thinking about today: hope.

In the original poem, and in the anthem, we find the same line, “Our hope is not yet lost.”

This is interesting. Imber did not write, “We will never lose hope,” or “We will always have hope,” or “We have hope.” He essentially wrote, “We haven’t lost hope yet”, “we still have hope,” as if our losing hope will come at some point, but just not yet.

And in this moment of sadness in a dark year, I ask myself, where is that point? When will hope be lost? Imber gives us his answer at the end of his poem with: “Only with the very last Jew, only there is the end of our hope.”

I think this is something worth remembering. Hope is in our heritage, in our culture, and by virtue of our ability to survive, is embedded in our DNA. Even on days like today, it is worth remembering that we always have hope.

Tragedy

On Sunday, the Jewish world received confirmation that six young, beautiful, hostages, had been executed by Palestinian terrorists:

Hersh Goldberg-Polin

Carmel Gat

Eden Yerushalmi

Alexander Lobanov

Almog Sarusi

Ori Danino

May their memories be a blessing.

First, let’s be clear: they were not killed by Bibi, Biden, Harris, Trump, the left, the right, Labour, Likud, or Meretz. They were killed by Palestinian terrorists in Gaza. Executed, shot just days before their bodies were recovered.

As word spread of this recovery, tears began to flow throughout the Jewish world. Hundreds of thousands of Israelis took to the streets to protest the government and failure to safely return our children home. Vigils were held in cities throughout the Diaspora, including right here at home, at Earl Bales Park. The Jewish world fumed and mourned, as the rest of the world sat idly by. The media reported on “dead”, not “murdered,” hostages, and the British Government decided that this was an appropriate time to limit arms deliveries to Israel.

On Sunday and Monday, funerals were held throughout Israel.

At Alex Lobanov’s funeral, his wife, who gave birth to their second child while he was in captivity, wept, and eulogized him as someone who loved life and freedom. “Love of my life…it is really true that God takes the best,” she cried. “Please come to me in my dreams, send me signs. Rest my sweetheart, now you can rest…You left here many people who love you…Please send me strength, I will be yours forever and ever until we meet again.”

At Ori Danino’s funeral on Mt. Herzl in Jerusalem, his brother Aharon asked how he could ever smile again. “In the last 330 days, I didn’t find any reason to smile. I didn’t find anything to hold onto or anyone to trust, apart from God. You were the pillar of the home, of your friends, and of myself.”

In Jerusalem, on Monday, thousands gathered for Hersh Goldberg-Polin’s funeral. In eulogizing him, his inimitable mother Rachel said, “I want to thank God in front of you all for giving me the magnificent present of Hersh for 23 years. I just wish it had been longer.”

She concluded,

OK sweet boy, go now on your journey. I hope it’s as good as the trips you dreamed about because finally, my sweet boy, finally, finally, finally, you are free.

I will love you and I will miss you every single day for the rest of my life, but you’re right here. I know you’re right here. I just have to teach myself how to feel you in a different way. And Hersh there is one last thing I need you to do for us. Now I need you to help us stay strong and I need you to help us survive.

On Sunday, before Hersh’s funeral, hundreds gathered at a community centre near his family’s home in Baka. Some led prayers, singing Avinu Malkeinu, other songs of mourning, and ending with Hatikvah. Some wouldn't sing Hatikvah because of their anger at the Israeli government. Others felt that it was inappropriate to sing about hope.

One of the attendees was Susi Doring Preston. She said that she usually steered clear of war-related events because they were too overwhelming for her. “Before, I avoided stuff like this because I guess I still had hope. But now is the time to just give in to needing to be around people because you can’t hold your own self up any more. You need to feel the humanity and hold onto that.”

Another community member, Guy Gordon, had said that efforts towards ensuring Hersh’s safe return had been an anchor for the community during the war. “It gave us something to hope for, and pray for, and to demonstrate for. We had no choice but to be unreasonably optimistic. Tragically, it transpired that he survived until the very end.”

At the bottom of the article where this was reported in The Times of Israel, a comment reads, “All we can hope for now is healing.”

There is talk in Israel and in the Diaspora, of losing hope. That this is all just too much. That the sadness is overwhelming. That we don’t know how much longer we can go on for. I get it, and also can't imagine the pain these parents and families feel.

To this, all I can say is, we have sadly been here before. And as Imber wrote, we cannot lose hope, until there is only one Jew left.

Seeking and finding comfort

For all of our history, we have sought and found comfort in our community.

Yesterday, I noticed on the various funeral notices, that the date was listed as “19 Menachem Av.” (This is a typo, as it should be the 29th). It is the Hebrew month of Av.

The name of the month, Av, literally means “father” in Hebrew. It is customary to add the name “Menachem”, before the name of the month, which means “comforter” or “consoler” because of the tragic nature of the month. On the 9th of Av, we commemorated the destruction of both Temples in Jerusalem, and the day is often considered the saddest day in Jewish history.

It is for this reason that the word “Menachem” or “consoler” is added on, to always remember that even in our saddest days, God, as our consoler and father, is there to comfort us.

On days like these, when the grief is overwhelming, and when many can be forgiven for feeling as though they’ve lost hope, we must be able to turn to our history, our traditions, and most importantly, our community, for comfort.

Od loh avda tikvatenu - we have still not lost hope. But that does not mean that we cannot cry. Afterwards, we must dry our cheeks, check on our friends and neighbours, and prepare ourselves for what comes next. No one has ever said that it is easy to be a Jew, but the burden is eased by never having to be Jewish alone.

Thank you for always being able to articulate what I am carrying in my heart. This is a beautiful article and I even learned something about Hatikvah that I didn't know. Thank you for your words of comfort, compassion and strength at a time that we all need it.

Beautiful. Sharing it here in Canada