We Jews have been too adaptable. We have been too eager to sacrifice our idiosyncracies for the sake of social conformity…Even in modern civilization, the Jew is most happy if he remains a Jew.

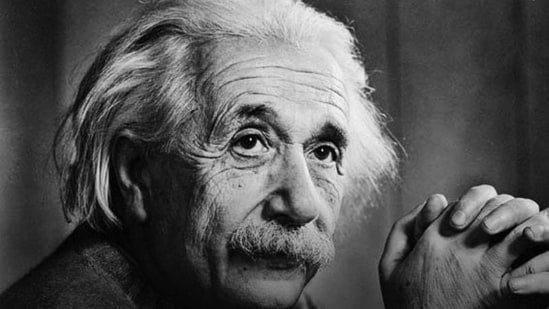

In an interview with George Viereck in Berlin in the early 1930s, Albert Einstein observed the above in response to the question: “Should Jews try to assimilate?”

This was a surprising answer coming from someone who had spent much of his time in Germany as a highly assimilated Jew. Despite some of his questions however about Jewish observance, Einstein proudly considered himself a part of the Jewish nation, and an ardent Zionist. He did not believe in assimilation, and was critical of those Jews who tried too hard to please others.

Inclusivity in Toronto’s Jewish community

Over the last several weeks, there has been a lot of talk in Toronto’s Jewish community about inclusivity. The term is obviously a buzzword, and it means different things to different people and institutions. At its simplest form, the notion of inclusivity is an effort to cast a wide tent, and ensure that as many people as possible can be included, regardless of their [insert defining features here].

But it is in the Jewish community in particular that this question of inclusivity creates the most confusion, at least to me. Inclusion in the Jewish community means different things to different people, as we in Toronto are blessed to have a diverse community. But, isn’t one of the defining features of Judaism a sense of exclusivity, instead of just inclusivity? How do we then square that circle to make sure not only that people see themselves in our community, but also make sure that we as a community do not broaden the goal posts too far, and let in every possible penalty kick? How do we ensure that we stand for something without falling for anything?

Secular Judaism (?)

Last Sunday I was privileged to speak at Limmud Toronto. I was there to speak about Sarah Aaronsohn, one of my favourite players in early Zionist history (more about her in another post). I got to U of T early, finished my last-minute preparations, and decided to poke my head into another talk taking place in the room next to where I would be speaking. The description mentioned “Secular Judaism” and my curiosity was piqued.

I sat around a table with approximately 20 others. The moderator introduced the panel, and they jumped into the subject matter of Secular Judaism.

The first speaker began that he comes from a line of proud Communists. Neither G-d nor religion played any role in his family’s home. It was forbidden. They did not celebrate Jewish holidays, and they did not engage in Jewish rituals. They do not participate in the mainstream Jewish community, and he believes that Israel is a racist state.

But, he reassured us, he was “very Jewish.”

The same went for the next speaker, and the next. The third panelist made clear that her allegiances lay not with the Jewish State, but with Palestinian nationalism. She was proudest when she got to take part in a “radical” Passover seder that acknowledged the plight of the Palestinians, and when she gets to teach “the other context of the Holocaust.”

My innocent ears had heard enough. Needing to maintain my composure for my lecture 15 minutes later, I got up and left. I never learned what the “other context of the Holocaust” was, and what are the defining characteristics of Secular Judaism.

I may be naive, and there may very well be readers out there who adhere to Secular Judaism, but I’m sorry: I don’t get it. How can one be Jewish if they are openly hostile to Jewish religious beliefs or rituals, reframe Jewish holidays to fit their fringe political agenda, distort Jewish history, have animosity towards Jews who do believe and practice these things, and reject the right of the world’s only Jewish state to exist?

In fact, why do they even want to identify as Jewish if they don’t believe in any of the above? (The cynic in me believes the answer to this question is so that they can ally themselves with our anti-Israel friends, and begin their speeches with “as a Jew…” for extra street-cred. But I digress).

A place in Judaism for inclusivity

Attending the first 20 minutes of this talk on Secular Judaism however was apt, because our community is now talking about inclusivity. I often wonder who should be considered a “Jew”, and who not. Today, support for the right of Israel to exist as a nation-state is engrained in the mainstream Jewish community. Must you be a Zionist, or at least not an anti-Zionist, to be considered a Jew? Are the Neturei Karta Jews? Sure, because they at least tick some of the other boxes. And do they think that I should be considered a Jew when I’m a Zionist who doesn’t keep Shabbat? I should hope so.

To be clear: lots of people should, and are, considered Jews, as they should be, and our diversity is a blessing.

But what about when people have opened up the definition of Judaism so broadly, that it is no longer possible to recognize a Jewish (or even Jew-ish) soul inside? What if the language of inclusivity in our community broadens to include every iteration of Judaism, no matter how secular, how anti-Zionist, how anti-religion/ous, just because this is now the spirit of the times? To me, this is troubling.

Jewish State or State of the Jews?

When Herzl’s Der Judenstaat was published in 1896, a question arose about the English translation of the German title: did it mean “The Jewish State” or “The State of the Jews”?

The translation had serious consequences. It can be argued that Herzl actually envisioned A State of the Jews: basically, a Germany on the Mediterranean, where people spoke German/Yiddish, waltzed on weekends, and did…other German things (ate strudel and shouted?). He was duly criticized by Ahad Ha’am, his most scathing critic, who suggested that Herzl was simply advocating for a country like any other, but filled with Jews.

On the other hand, and what Ahad Ha’am wanted to see, was a Jewish State (he actually just wanted a Jewish cultural home, not a state). But a Jewish State would be a state infused with Judaism, and that took its cues from our religious traditions and values. This is the state that Israel would eventually become, even if some of those Jewish traits are criticized by secular Israelis (note, not Secular Jews), or by Israel’s non-Jewish population.

A Jewish community, or community of the Jews?

This distinction however between a Jewish State and a State of Jews is important in a Jewish community like Toronto. The nuance has practical implications to our institutions, where the push for inclusivity within a faith community that is designed to be exclusive is confusing.

Take the day schools for example: in any effort to define the inclusivity they strive for, they must account for the fact that Judaism is a religion full of red lines. And yes, we are first and foremost a religion, from which all other aspects of our community (peoplehood, nationhood, community, culture, traditions) originate. What those red lines are, and where they are to be drawn is a necessary exercise for any institution seeking to take on the mantle of inclusivity. Lest the schools become havens for “Secular Judaism” (the type referenced above), which I really don’t believe they want to be, they do need to choose where to draw the line.

An example of a red line in this context is, to pick a low-hanging fruit, kosher food. I imagine most of, if not all, Jewish schools in Toronto will not actively sell or promote non-kosher food in their institutions. This is a clear red line that has been drawn.

Really, any institution that is non-Orthodox, that decides by virtue of their traditions that they will not adhere strictly to the Halacha, but that they will open up to more exceptions, needs to think about this. This is the history of our religious development, and is the reason why we have different streams of Judaism, and different levels of observance of our faith. But every group that is not strict in its adherence to the mandate of the Torah, for example, needs to be more thoughtful, not less, as they must consider where to draw their red lines, where their inclusivity ends, if at all, and what they believe to be outside the bounds of their Jewish identity.

Change in moderation

As the world around us changes, often far too fast, we will change too. But the extent of that change is something that must be measured and done within the confines of what we believe.

There is huge merit to the value of inclusivity. We have an incredibly diverse community, one of the most diverse in the world I would argue, and only recently have we truly begun to embrace that. As we become more aware of the need to be inclusive, we naturally look around and realize the extent of our diversity, of Ashkenazi, Sephardi, and Mizrahi Jews, and those with varied customs and traditions. Our institutions have morphed to take that diversity into account, and we are the better for it.

There must be a purpose, however, for our inclusivity. Our goal in the end is never to keep people out, nor to be narrow minded, but it is to keep sacred the community to which we belong.

Love thy neighbour, be respectful, save a life, and fix the world: these are all the classic mantras that we tell our children about how to live a Jewish life. But there is much more than these simple universal lessons. There are rules and prescriptions that we can, and in my opinion should, adhere to because Judaism contains so much that makes this world a beautiful place. A Jewish father, for example, is responsible not just for raising a mensch, but there are three explicit things that ever Jewish father is required to teach his children: the Torah (i.e. give them knowledge), a trade (i.e. how to make a living), and how to swim (i.e. how to save themselves). This is the prescriptive nature of our religion, and speaks to specifics that are often overlooked but that do make a difference.

Jewish life is much more than generalities, and we happen to come with a lot of specifics. Our exclusivity has kept us around all these years, and we cannot afford to shy away from it.

Our exclusivity does not stand contrary to our inclusivity, as they ought to be goals that we pursue in tandem. They need not negate each other, but they are each more effective when they complement each other. We need not exclude others to be who we are, but we ought to be proud while being distinctly Jewish, and understand that there is nuance in our religion that enables us to both walk and chew gum.

Einstein was concerned that Jews in the early 1930s had become too willing to set aside their traditions to satisfy the yearnings of assimilation. He believed however that being a Jew placed on one’s shoulders a specific role, and mission, and he was apt in this thinking then, as now.

As Alexander Hamilton quipped to Aaron Burr (in the play, not reality): “If you stand for nothing, Burr, what’ll you fall for?”