Wielding the sword

The word gladiator comes from the Latin gladius for “sword.” The word evokes the Roman Coliseum, fighters with their swords forced into battle with other slaves or even wild animals, and of course Russell Crowe standing up to a corrupt Caesar. “Are you not entertained??” he shouts to the unsympathetic crowd who seem unimpressed with his latest feat.

When I think about gladiators, sure, the Jews are not the people who come to mind. Though there is a history of Jewish gladiators - 20,000 were brought to Rome by Titus after the destruction of the Second Temple, so its no surprise that some gladiators were Jewish - we are more known for being the slaves who built the Coliseum, rather than those who fought in it. But a meme was recently circulated online that made me think about this and the idea of Jewish strength.

It was this:

This definitely made me laugh when I first saw it, and after seeing it I opened WhatsApp and sent it to a bunch of friends. However, it has been in the back of my mind since then because it prompted me to think about Jews and power. Not just power in its raw form as a ripped husky, but the way that Jews did, and can still, wield their swords.

Obviously, this meme plays up the stupid generalization about Jewish weakness that has been passed down over the centuries. Today, it fails to account for the actual Jewish strength that we have in Israel and the IDF, the power that we wield as an organized Diaspora, and the positive influence that we have always had on the world (not in the antisemitic conspiratorial sense but you know, the good kind).

Nevertheless, it is not just others, but often we, as the Jewish community, who need a refresher about the ways that we have wielded positive power. To understand our potential means to reflect on our accomplishments, and we have lots of those of which to be proud.

Ben Ferencz

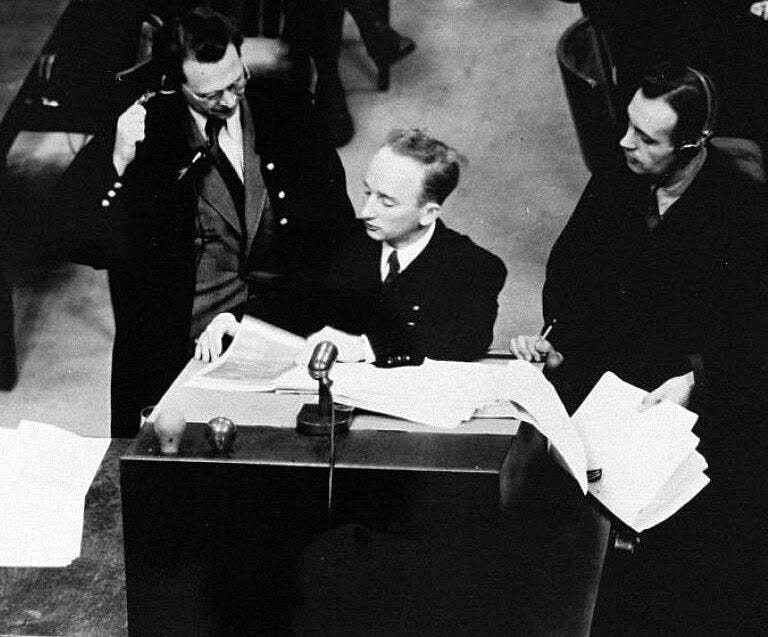

On April 7, 2023, the legal gladiator Benjamin Ferencz died at the age of 103.

Ferencz was the last living prosecutor of the Nuremberg trials. At the age of just 27(!!) he led part of the legal battle against members of the Nazi Einsatzgruppen (killing squads), who perpetrated the Holocaust-by-Bullets across Eastern Europe during World War Two.

Prior to his peaceful death in Florida this past week, Ferencz led a fascinating life.

Born in Transylvania in 1920, when Ferencz was just 10 months old his family fled Europe to avoid the persecution of Hungarian Jews by the Kingdom of Romania. His family settled in New York. He attended the City College of New York, and then enrolled at Harvard Law. Graduating in 1943, he promptly enrolled in the US Army, and by 1945, was transferred to General Patton’s Third Army HQ. There, he was assigned to a team tasked with gathering evidence of Nazi war crimes. He saw the concentration camps and their victims with his own eyes, no doubt imagining how his forward-thinking family members had been spared this cruel fate by their decision to leave Europe 25 years earlier. As he accumulated evidence, he grew determined to use the law to bring the perpetrators of evil to justice.

He was soon recruited to join the prosecution team at the Nuremberg Trials. At 27, with no prior trial experience (not even one), Ferencz was appointed the chief prosecutor of the Einsatzgruppen Case.

On July 29, 1947, the 24 defendants of the Einsatzgruppen Case were indicted for their role in murdering between 723,661 and 1 million people, “as part of a systematic program of genocide.” On April 8, 1948, the Nuremberg Tribunal found 20 of the defendants guilty on all three counts of: crimes against humanity, war crimes, and being members in organizations declared criminal by the International Military Tribunal. 14 of the 20 were sentenced to death.

After the case (now 1 for 1 with his trial experience), Ferencz remained in Germany with his wife Gertrude. He helped set up reparation and rehabilitation programs for Nazi victims, and played a role in the negotiations that led to the controversial Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany in 1952.

He later returned to the United States with his family where he worked for several years in private practice. He then began working for the institution of an international criminal court, devoting his life to the creation of a body that would one day prosecute crimes against humanity and war crimes. He taught international law at Pace University, and was heartened when the International Criminal Court was eventually established in 2002. He was now 82 years old.

Ferencz approached international law as a purist. He believed that the law should apply to everyone, regardless of politics or place on the world stage. Democracies were to be held to the same standards as autocracies, and though he understood the nuances of the law, he believed that if there was to be an international criminal legal regime, that it should apply equally to all.

Ferencz was a legal giant and was in fact not only active in his advocacy but also feisty about his cause until his last days. His motto was “law not war” and was his life’s mission.

Reading the tributes to Ferencz over the last week has led me to think about his role wielding Jewish power, and the context in which he raised his sword. Having seen the death camps first hand, he could have retreated to America and led a different life, but he found a calling and a cause through which he was already standing on the shoulders of two particular giants.

Raphael Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin was another Jewish lawyer who found his strength in one of history’s darkest times.

Born in 1900, Lemkin grew up keenly aware of the peril that surrounded Eastern European Jewry. Always asking questions, Lemkin made a startling realization while in law school at the University of Lvov in 1921.

He heard that an Armenian assassin, Soghomon Tehlirian, had recently murdered Talaat Pasha, one of the three pashas of the Ottoman Empire responsible for the Armenian Genocide. With Tehlirian on trial for murder (he was eventually aquitted), Lemkin asked a professor why a person responsible for one death was on trial for murder, whereas the deceased Pasha, a man responsible for the murder of over 1 million, walked free in Berlin. His professor observed that there was no law in existence that could be used to prosecute murder on such a huge scale. Unsatisfied with that answer, believing it was just a “crime without a name,” Lemkin set to work.

Lemkin was proud of his Jewish heritage. It is said that Lemkin’s legal theories drew on traditions of Jewish law which do not generally view the law as a strict instrument of state control over individuals, or something outlining punishments for violations (though it sometimes does). Instead, Lemkin saw the law as a moral and normative force for cohesion to bring about a shared sense of obligations and duties between people. This is how he believed communities came into existence.

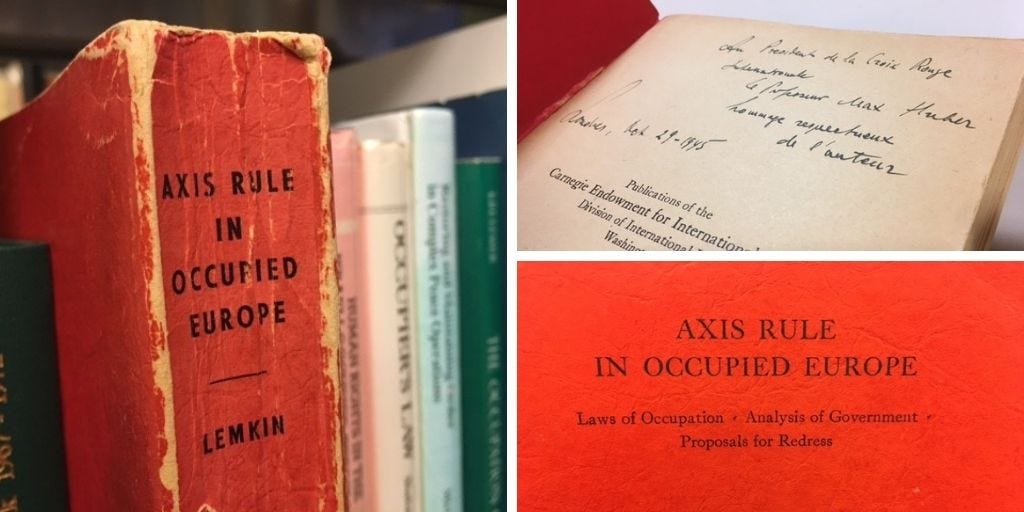

Starting in the early 1920s, Lemkin devoted his energies to the creation of a legal regime for the punishment of mass murder. His work sadly foreshadowed the Holocaust, but WWII certainly accelerated his efforts. Once safely in the United States, in 1943 he published Axis Rule, in which he coined a new word, “genocide.”

Genocide meant the intentional and complete (or attempted) destruction of an entire group of people. Understanding the plight of Europe’s Jews at the time, Lemkin sought to create a legal regime to hold not only the Nazis, but also other future mass murderers, responsible for their crimes. On account of his efforts, the Genocide Convention was signed into law on December 9, 1949, just one day before the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (also drafted by a Jewish lawyer, Rene Cassin of France).

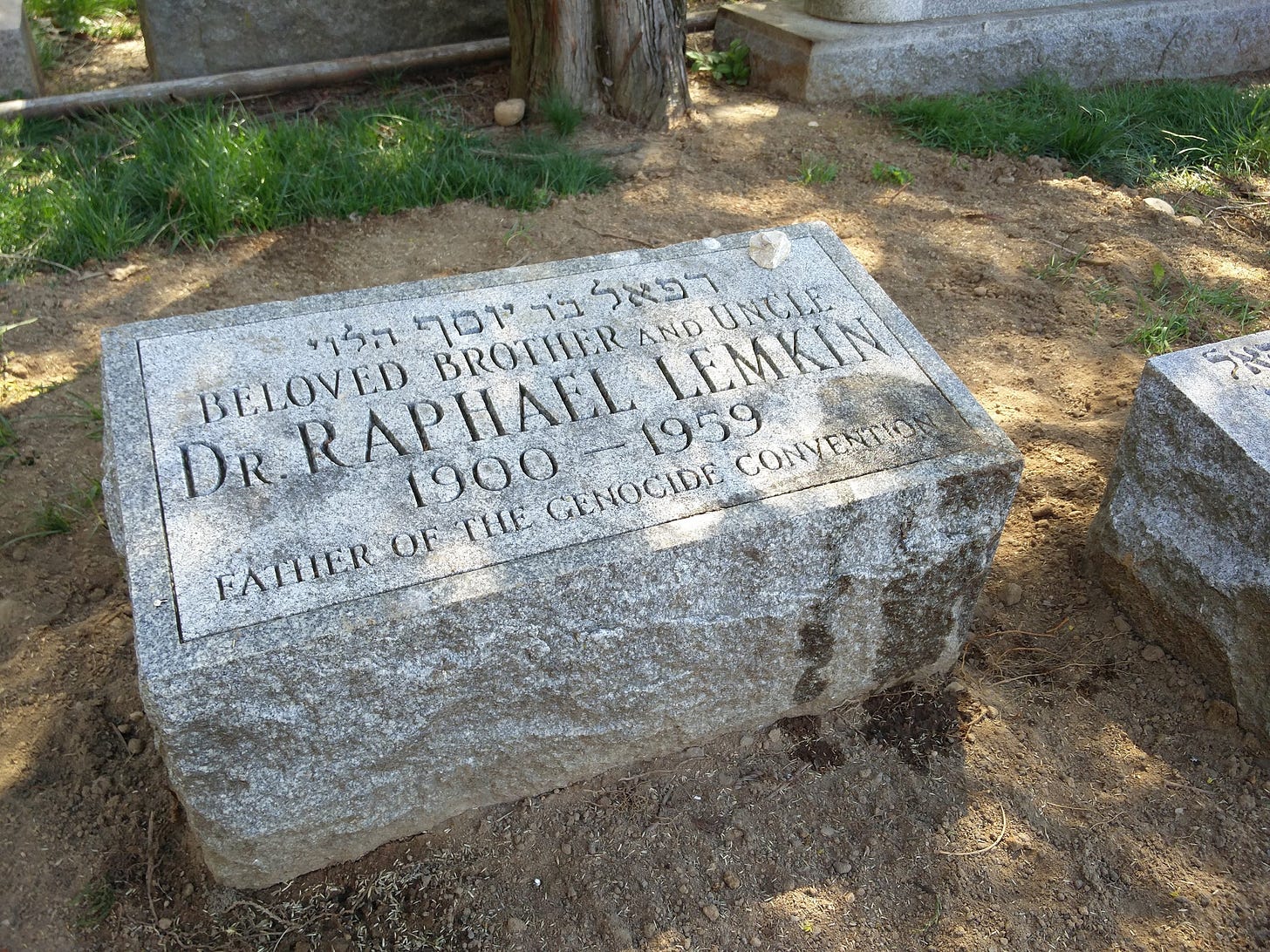

The adoption of the Genocide Convention did not end Lemkin’s efforts. By that time, Lemkin had learned that 49 members of his family had been murdered in the Holocaust, and he was motivated to get as many countries as possible to ratify his convention. He was still working hard to achieve this goal when he suddenly died at the age of 59 in New York. Dying a woefully misunderstood man, only seven people attended his funeral.

The first conviction of genocide was secured 49 years after the passage of the Genocide Convention when Jean Paul Akayesu, a Rwandan genocidaire, was sentenced at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Afterwards, Lemkin’s legacy found new light, and his story was given a new life.

Hersch Lauterpacht

Our third fighter was Hersch Lauterpacht. Lauterpacht and Lemkin both grew up in Lviv (now in Poland), studied at the same law school (though were in different classes), lost many family members to the Nazis (all of Lauterpacht’s European family members perished), and believed in the power of the rule of law. They were both there at Nuremberg helping the prosecution, and one can just imagine Lauterpacht, Lemkin, and Ferencz enjoying a coffee together in the breakroom while establishing norms of human rights that would be used through the next 80 years. In fact, Lauterpacht crafted the language of the Nuremberg Charter that enshrined crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression in modern international law. The international lawyer Philippe Sands wrote an exceptional book about Lemkin and Lauterpacht, East West Street, which is well worth the read.

Though Lauterpacht and Lemkin were not close, they each developed their legal theories parallel to each other in the context of the Holocaust.

Lauterpacht developed the new law of crimes against humanity. Lemkin’s law of genocide was broad, and emphasized the attempt to eradicate groups of people, whether in times of war or peace, and focused on the acts perpetrated against individuals. In contrast, Lauterpacht’s crimes against humanity sought to define and judge a state’s actions according to a new set of ideas about unacceptably harsh and consequential wartime behaviour. This could lead Nazi leaders to be charged, convicted, and executed at Nuremberg. Indeed, they were.

Lauterpacht went on to be a member of the United Nations’ International Law Commission, and a judge of the International Court of Justice. Notably, in 1948, he was asked by diplomats in the Yishuv to help write Israel’s future declaration of independence. By May 1948, he had produced a document, parts of which made their way into the final Declaration of Independence signed in Tel Aviv on May 14, 1948.

Lauterpacht died in May 1960 a giant of the legal world. His legal decisions are still cited today for the precedents he set in international law.

What we do in life echoes in eternity

Hold the line! Stay with me! If you find yourself alone, riding in green fields with the sun on your face, do not be troubled. For you are in Elysium [Heaven], and you’re already dead! Brothers, what we do in life echoes in eternity.

At the start of Gladiator, Crowe’s Maximus tells his troops that what they do in life will echo in eternity. He asks them to imagine where they will be after the battle, and if they do, they will live and it will be so.

Like Roman gladiators, Ferencz, Lemkin, and Lauterpacht were forced into their roles as they could not turn away from the horrors of the Holocaust and the perceived injustice of impunity. They were committed to crafting and enacting 20th century justice. Once forced into those roles, they fought with all their might, imagining what would be after the battle.

Though the jury is still out on whether the 20th century’s human rights legal regime has been a truly effective one (there has been no dearth of atrocities or impunity since WWII), one cannot question the impact that these three Jewish lawyers had on the system. They were not armed with brute strength, but they brought to the table the weapons they could wield. Passion and focus strengthened their determination, and what they did in life has echoed through the years.

Ferencz, Lemkin and Lauterpacht found strength at a time of Jewish weakness, and look what they did with it. It behooves us all to consider our own circumstances as a people and as a community, take stock of what we have in our arsenal, and wield our swords diligently to fight for what we believe is right.