Salo Baron was described by many as the 20th century’s greatest Jewish historian. He taught at Columbia University from 1930 to 1963, and hoo boy would he be surprised at what has become of that institution today.

Baron was born in Tarnow, Galicia in 1895, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He received rabbinic ordination in Vienna at age 25, and earned three - yes three - doctorates from the University of Vienna: in philosophy, political science, and law. Show off.

The inimitable American Rabbi Stephen Wise eventually persuaded Baron to move to the United States to teach at the Jewish Institute of Religion, and in 1930 he was appointed the Nathan Miller Professor of Jewish History, Literature, and Institutions at Columbia University. He basically initiated the teaching of Jewish history as an academic field in American universities.

After WW2, Baron ran an organization established to collect and distribute heirless Jewish property in the American occupied zones of Europe. He distributed hundreds of thousands of books, archives, and ceremonial objects to libraries and museums in Israel and the United States, whose previous owners had been murdered in the Holocaust. In April 1961, he testified at the Eichmann Trial in Jerusalem, explaining that in his birthplace, Tarnow, where there had been 20,000 Jews before the war, there were now no more than 20. He lost a sister and his parents to the Nazis.

As if he didn’t already have more degrees than a thermometer, throughout his later life he received more than a dozen additional honorary degrees from universities throughout Europe, Israel, and the United States. He died in 1989 at the age of 94.

Lachrymosity

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, lachrymose is an adjective, meaning “given to tears or weeping” or “tending to cause tears.” It comes from the Latin “lacrimosus”, from the noun “lacrima” meaning “tear.”

Sad. It means sad.

And historians could easily be forgiven for describing Jewish history as lachrymose. One need only scratch the surface of Jewish history to discover a rich tradition of suffering, of sadness, of an impossibility of acceptance, and of a plethora of blood shed and tears wept. Indeed, our existence over the last year alone could be forgivably described as lachrymose without debate.

An earlier historian, Heinrich Graetz, essentially described our history this way. A 19th century Jew, having spent his life almost exclusively in Russia and Bavaria (later Germany), Graetz is best known for writing History of the Jews, a remarkable work in which he penned a unified national history of the Jewish people across the globe. He basically undertook the arduous task of putting together an incredible number of Jewish sources into one chronological narrative of history, called “the best single introduction to the totality of Jewish history” at the time.

Despite the majesterial way in which Graetz presented Jewish history however, it was described by some as treating the Jewish experience as essentially “suffering and spiritual scholarship.” In some ways, perhaps unavoidably, Graetz described so much of the hardship of being Jewish throughout the centuries, that the actual difficulty of being Jewish characterized the entirety of his history. Later historians took issue, and considered this description of our history as inaccurate.

Baron, for one, later took issue with what he called the “lachrymose conception of Jewish history” that Graetz wrote. Though respectful of Graetz’s history and intellect, Baron rejected Graetz’s focus on the suffering and persecution of the Jewish people, and argued that our history should be defined instead by the creative and intellectual responses that Jews had to their historical challenges. Baron was not denying that the Jews suffered throughout their history, but rather sought to affirm Jewish history and life in all its diverse, and frankly amazing, aspects.

Smarter people than me have written much about this over the last 100 years, and it is an interesting thought experiment to consider what emotions first come to mind when you think about Jewish history. You would be forgiven, certainly, for being compelled to consider our history as dark; but it is important to consider the light.

Dichotomy

One such way to realize this, is to think about a wedding.

This weekend, I attended my cousin’s wedding. It was totally wonderful. 200 people in a beautiful room (at the Magen Boys’ Newage Event Centre in Toronto - check it out) celebrating love, happiness, and perhaps most importantly, the bright potential of the future.

A Jewish wedding ceremony always innately contains some dichotomy of light versus darkness. Indeed, the very act of breaking a glass at the end of a wedding is to remember the destruction of the Temple, and what we are missing in our Jewish lives. But the glass is broken, and it is immediately followed by the bride and groom kissing, and ecstatic shouts of “mazel tov!” from the crowd. We invoke one of our darkest collective memories immediately before celebrating our happiness in the present. We want the absolute best for the new couple in the future.

Weddings over the last year however have also included other reminders of darkness, not of our past, but of our present. At several moments during this weekend’s wedding, the war in Israel was invoked, as were prayers and blessings to return our 101 hostages still held in Gaza. And no one blinked an eye. It was not strange to invoke such suffering at a time of such joy: this is the reality of Jewish history and the Jewish moment today. We acknowledge sadness at the same time we celebrate joy. We conclude our wish to bring back the hostages with a shout of “amen!” and then continue on with the bride and groom’s first dance.

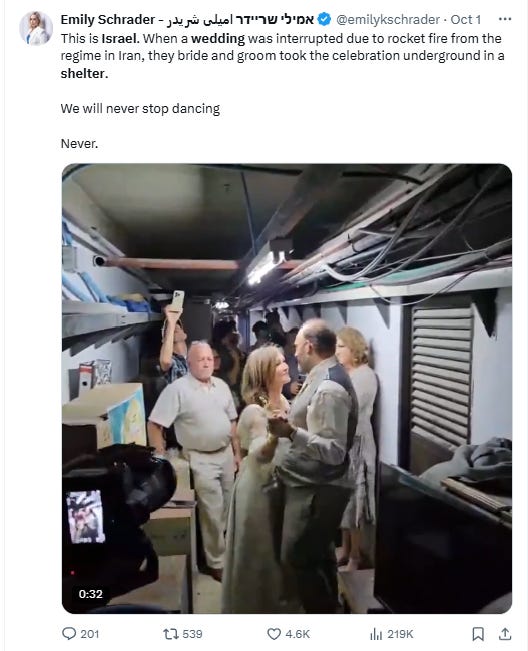

I don’t think there is any strangeness to this at all: for all of our history, Jews have celebrated weddings including during trying times. In our tradition and Jewish law, it is imperative to celebrate at a Jewish wedding, which is not supposed to be disrupted by a time of mourning a close family member or other cause of sadness, because you should not cause distress to the bride or groom (of course, with all Jewish laws, there are exceptions). We celebrate life and the beginning of lives together. Just look at all the weddings that have had to take place in Israel over the last year, some interrupted by rocket attacks from our enemies, where the bride and groom took a brief break in a nearby bomb shelter, before getting the all clear and proceeding to dance the night away immediately afterwards.

The wedding this weekend, at least to me, was a microcosm of the broader dynamics in the Jewish world. The ongoing dichotomy and duality of sadness and happiness are always intermingled, while we try to sort out our feelings and figure out how to express one, or the other, or both at the same time.

In the first few months after 10/7, I recall thinking that I had never been that sad before in my life. It was a time when I felt guilty smiling, laughing, celebrating, or doing almost anything joyful knowing that so many of my brothers and sisters in Israel and the Diaspora were mourning dead, missing, or psychologically abused relatives. How could we celebrate then knowing that hundreds were detained and being mentally and physically tortured in Gaza? The thought of the hostages still crosses my mind whenever I feel like I’m getting too happy. And it’s an important reminder, and it is why we wear yellow ribbons and dogtags - to always be reminded.

But our lives have gone on. We have continued to celebrate at weddings, bar/bat mitzvahs, births, and other important milestones. And it’s not that we’ve moved on as though we have forgotten or minimized the tragedy of the post-10/7 world, but I think that celebrating when the moment presents itself is intensely important to our community too. At the very least, when the hostages are returned to us, we want to show them that we can still be happy, and that there is something worth returning to.

This is what it has always meant to be a Jew. To acknowledge the sadness that can often overcome us, to be vigilant to the risks that can haunt us, but to rise to the challenge of being happy when the opportunity presents itself to us. And so I think a reminder at a wedding of the tragedy of the hostages, or the broader ongoing war, is deeply important, as is what comes next. Only through that elation do we defeat the lachrymosity that we too often feel.

As we sing at each wedding, “It will yet be heard in the cities of Judea and the parts of Jerusalem: sounds of joy and sounds of gladness, the voices of the groom and the bride.”

עוֹד יִשָׁמַע בְּעַרֵי יְהוּדָה וּבְחוּצוֹת יְרוּשָלַיִם

קוֹל שָשוֹן וְקוֹל שִמְחָה

קוֹל חָתָן וְקוֹל כָּלָה

Mazal tov to L & A.

Am Yisrael Chai

Perhaps the only part I have to comment on, Adam, is a feeling I often have when reading your articles and I wonder deeply: are there actually people smarter than Adam? Your articles and teachings are brilliant and I thank you.