Something light for the end of the year, right?

We have all heard the word genocide tossed around in the last few months. And it has been used astutely to describe true attempts to wipe a people off the earth: The Chinese reeducation and decimation of the Uyghers, and the Janjaweed militias in Darfur killing ethnic African tribes.

I am being sarcastic, of course, because today, the charge of genocide is directed once again only against the Jewish State. Apparently, Israel is committing a genocide against the Palestinian people in its effort to root out the Hamas terror infrastructure in the Gaza Strip.

Let’s just be perfectly clear from the outset: this is a lie. A modern day blood libel.

The ridiculous way the word genocide has been tossed around of late reminds me of an event at York University in 2005. Hillel@York had invited Alan Dershowitz to give a lecture about his new book The Case for Peace. During the question period, one of the anti-Israel protestors who had embedded himself in the crowd stood up and said, “Professor Dershowitz, I believe that occupation is terrorism.” To which Dershowitz quickly responded, “Alright, so you’re just changing the definition of a word, fine, so I can do that too: milk is bread.”

This is exactly what has been happening online and in the zeitgeist today. People are just applying this term genocide to any situation of which they disapprove, because they know its the worst allegation to make.

Take these two recent examples, and of course my witty late-night responses on X:

Or this:

Aside from the sheer stupidity of what is happening, what has gotten me really hot and bothered is the fact that the term and definition of “genocide” as a legal definition comes from a particular time and place, and was in fact intended to describe the most horrendous act that humans can do to other humans.

When applied correctly, the genocide label is intended to make the world a better place by bringing perpetrators to justice and deterring future acts.

Raphael Lemkin

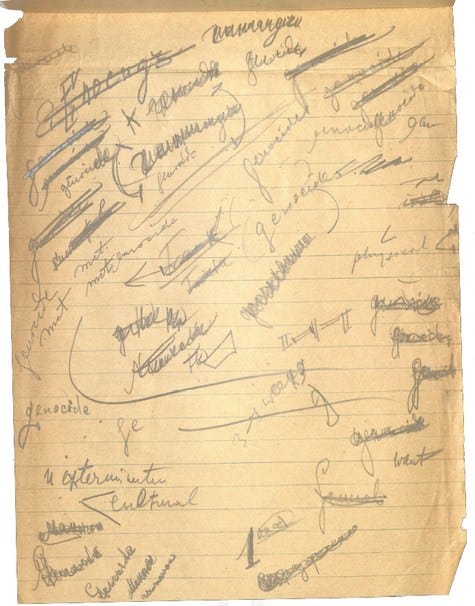

Raphael Lemkin coined the word genocide in 1944. It is a combination of two Greek words, geno = race/tribe, and cide = killing, intended to convey the intentional killing or attempt to kill an entire group.

Raphael Lemkin was a unique and quirky individual. Born in Eastern Poland in 1900, growing up amid war and turmoil – with Polish territory constantly changing hands – he became obsessed with death and destruction. He knew that, as a European Jew, he could never let his guard down.

By the early 1920s, Lemkin was a law student at the University of Lvov. On March 15, 1921, there had been an assassination in Berlin: a young Armenian named Soghomon Tehlirian, walked up behind the former Turkish Interior Minister Talaat Pasha, and shot him in the head. Tehlirian had lost his entire family in the Armenian massacre (what would later become known as the Armenian Genocide), and he had just assassinated the man responsible for their deaths. For the crime of avenging his family’s murder, Tehlirian was put on trial for murder.

Lemkin followed this trial closely and famously asked a professor why someone responsible for a single murder was on trial, whereas an individual responsible for a million murders (Talaat Pasha) had been walking free in Germany?

His professor answered that no law then existed to try someone for mass murder on such a scale. He said,

Consider the case of a farmer who owns a flock of chickens. He kills them, and this is his business. If you interfere, you are trespassing.

Wholly dissatisfied with this answer, responding that “the Armenians are not chickens,” Lemkin turned his mind to this legal lacuna, and decided that he would be the one to define the crime without a name. In prophetic anticipation of what lay ahead for Europe’s Jews, he immediately got to work in developing a clear definition of what he would later call “genocide”.

In 1926, a second event transpired that further prompted Lemkin on his legal crusade. In September, the notorious Ukrainian antisemite and pogrom-organizer, Symon Petliura, was assassinated by Sholom Schwartzbard in Paris. Schwartzbard, like Tehlirian, had sought to avenge crimes committed against family members, by assassinating the man ostensibly responsible for their deaths. In an article, Lemkin called Schwartzbard’s actions a “beautiful crime”, stating that the problem was that, “there was no law for the unification of the moral standards of mankind in relation to the destruction of national, racial and religious groups.”

As a lawyer in Warsaw in 1933, Lemkin was appointed to be a state prosecutor, while at the same time pursuing studies in philology (the study of the development of languages) and philosophy. By the time of his death, Lemkin was fluent in 14 languages, a testament to his desire to literally scour the globe in search of the perfect word to describe the most horrific of crimes. If you’re curious, those languages were Polish, Russian, French, Italian, Hebrew, Sanskrit, English, Spanish, Arabic, Yiddish, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, German, and Swedish.

Throughout the 1930s, he watched in horror the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany. With his penchant for pessimism, he grew to believe that the Jewish people would suffer untold horrors at the Nazis’ hands. He examined the Nazis’ racial policies and laws in each country they conquered. He took them at their word about their genocidal intentions.

After the war broke out in September 1939, he traveled home to his family in Eastern Poland, begging them to flee to America with him. They refused to do so, opting to remain at home, incapable of imagining the horrors coming their way. Lemkin noted that during this visit, “It was like attending their funerals while they were still alive. The best of me was dying with the full cruelty of conscience.” By the end of the war, 49 members of the Lemkin family had been murdered by the Nazis.

Defining a crime with no name

Lemkin fled to America. Throughout his travels, he collected whatever documentation he could find of the Nazis’ racial crimes, intent on publishing a book documenting their specific acts and the intentional way in which they sought to decimate the Jewish people of Europe. Intention, of course, is a critical element of almost any crime.

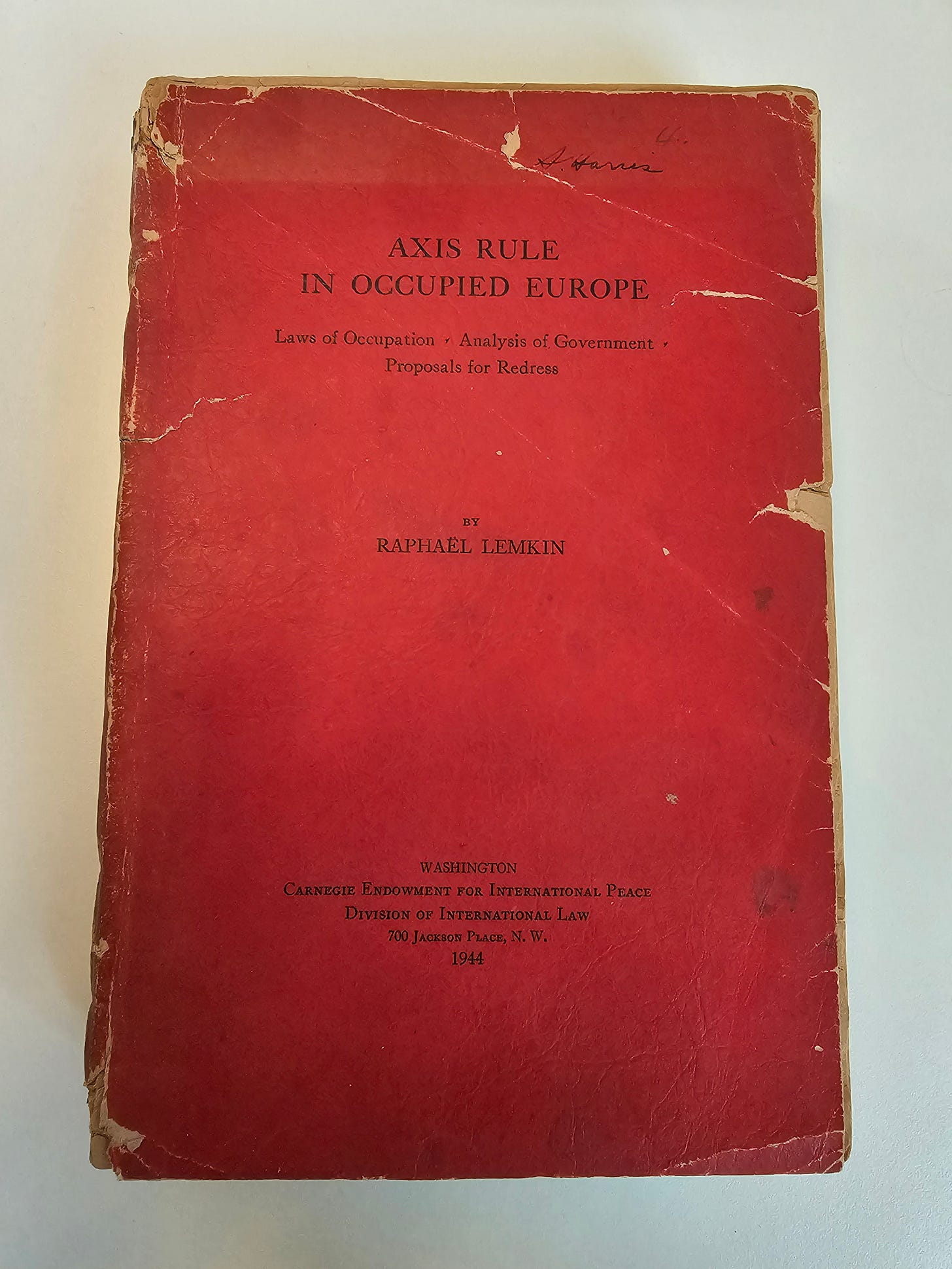

While in America, working first as a law professor at Duke and Yale Universities, then as the Head Consultant to the Foreign Economic Administration, then as Foreign Affairs Advisor to the US State Department, and then as a lecturer at the School of Military Government in Virginia, Lemkin wrote Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress.

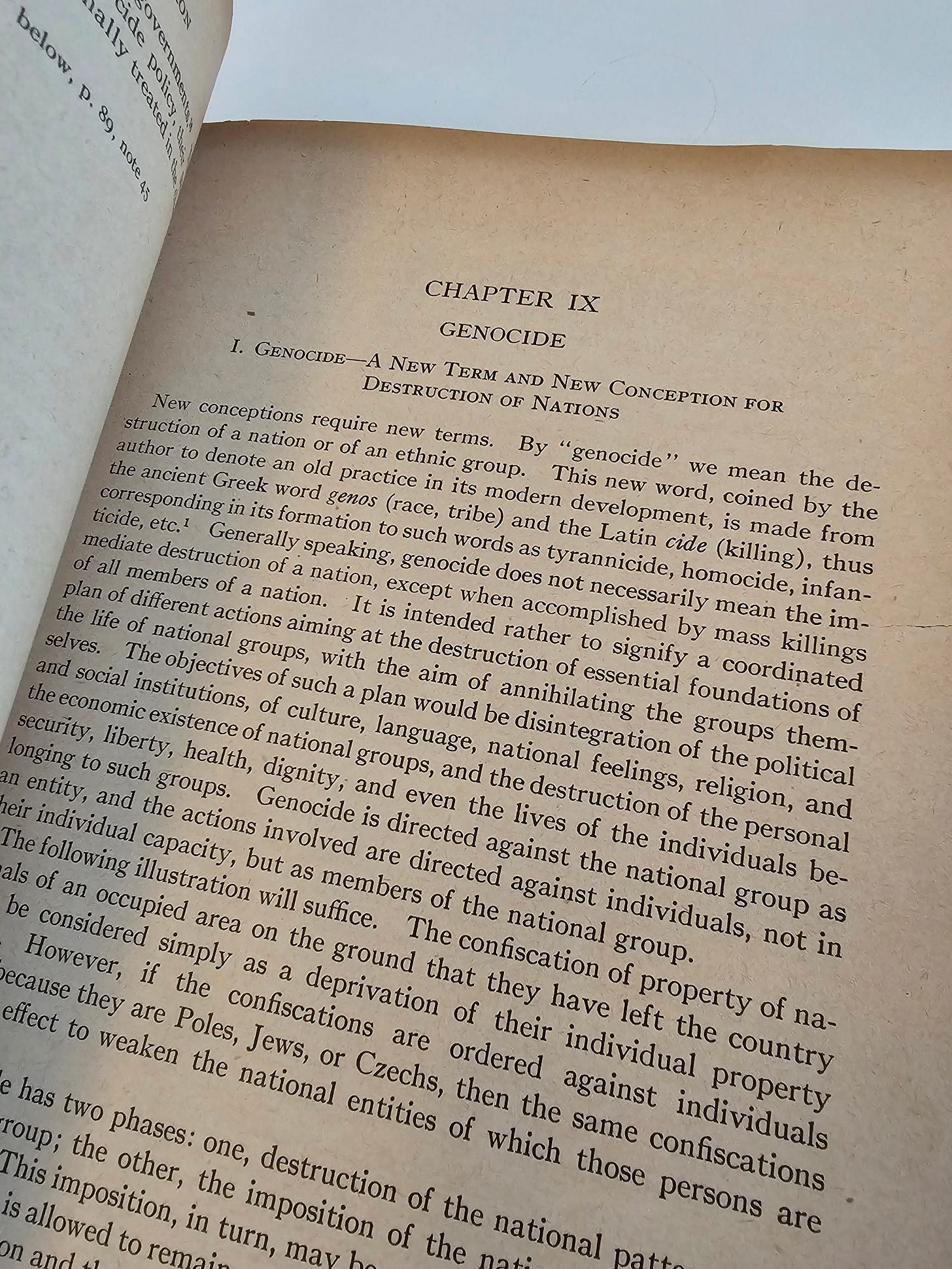

Published in 1944, Lemkin coined and published for the first time, the word “genocide” and proposed a legal definition:

Genocide is a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves...

Genocide has two phases: one, destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor. This imposition, in turn, may be made upon the oppressed population which is allowed to remain, or upon the territory alone, after removal of the population and colonization of the area by the oppressor’s own nationals.

Though thoughtful, Lemkin’s proposal was not without controversy. People were of course receptive to the idea of defining the most horrific of crimes. But, concern was raised about making Hitler’s crimes the benchmark against which others would be measured. There was also confusion, in that people assumed that according to Lemkin’s definition, genocide occurred only when the perpetrator of the atrocity could be shown to possess the intention to kill every last member of the group. Finally, some were critical of Lemkin’s perceived naivete: after all, a word is just a word.

Continuing with his advocacy, Lemkin successfully advocated for the new crime of genocide to be included in the Nuremberg Tribunal indictments. There, the definition of genocide was honed, to include the following:

Any of the following acts, committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

Killing members of the group

Causing serious or bodily harm to members of the group

Deliberately inflicting on group conditions of life calculated to bring about physical destruction in whole or in part

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within group

Forcibly transferring children of group to another group

To be found guilty of genocide, you must:

Carry out one of the above acts;

With the intent to destroy all or part of

one of the groups protected.

Unfortunately, none of those on trial at Nuremberg were successfully convicted of genocide. On December 9, 1948, however, after relentlessly advocating at the nascent United Nations, Lemkin succeeded in having the Genocide Convention adopted by the world body. Just three years after the end of the Holocaust, the world declared that it would no longer be silent in the face of mass murder.

Lessons for today

So, why this lengthy history lesson at the end of 2023?

Well, it is important to remember that words have meaning. In today’s world, too much is dictated by emotion. Doomscrolling through X or Instagram, we spot key words or phrases, and the way they are presented, with a sexy infographic or an attractive influencer, can often mold the way we feel about a situation. But words have meanings, and there are legal definitions attached to words too.

Genocide is a word that comes fully loaded. It was coined in a specific time and place, by someone who not only sought to define a crime then without a name, but who wanted to ensure that people were brought to justice for committing that crime. Lemkin and others laboured to give genocide a particular legal definition that was eventually codified on the world stage.

Genocide is an intentional effort to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, or religious group. What is happening in Gaza today, is not a genocide. If it was, the war would have ended on October 8, 2023, with 2 million dead Palestinians. Israel would not have sacrificed the lives of 164 IDF soldiers, and those hundreds of thousands displaced in Israel would have returned to their homes.

But it is not. The war has lasted over 70 days. Tragically, thousands of Palestinians have died, including many thousands of terrorists, because Hamas has turned the entirety of Gaza into a terror-state. Their terror tunnels run beneath neighbourhoods and critical infrastructure, they use hospitals as military bases, they maintain weapons caches in schools, and they launch rockets from residential locations. These Palestinians have not died because of indiscriminate IDF attacks, and Israel has never expressed an intent, ever, to decimate the Palestinian population. Any civilian death is tragic, but unfortunately, civilians die in war.

Similarly, the entirety of Israel’s conflict with the Palestinian people since 1948 is not a genocide. Israel has never sought to destroy the Palestinian people. Instead, they have sought a sustainable status quo, where they could live side-by-side with them without constant fighting. These proposals have been turned down by the Palestinians many times. During that time, the Palestinian population has ballooned, a fact that on its own, defies the allegation of genocide.

In contrast, the massacre of Israelis on October 7 was an attempted genocide. For decades, Hamas has sought to destroy the entirety of Israel and its inhabitants, and October 7 showed what would happen if they were given the opportunity. They sought to perpetrate a genocide of Jews that was thankfully thwarted.

Part of me thinks that this whole article is unnecessary because it is so obvious that what is happening in Gaza today is not a genocide. But the word continues to trend, it still appears on placards and hashtags, and is taken way out of context by those alleged “academics” brainwashing students on Ivy League campuses.

It is thus imperative that we understand what is and what is not genocide. In today’s emotionally-driven discourse, we cannot allow ourselves to be taken in by the hyperbolic language of the masses. It distracts from what is really happening on the ground, whether in Gaza, China, or Darfur. It diminishes suffering, hardens the hearts of critics, and further complicates an already complicated world.

I know it is too much to ask, but on the eve of 2024, reason and logic, not clicks and likes, should determine our discourse’s path forward. To that end, as we enter the new year, we can only ask for a swift resolution to this conflict, for the return of those remaining hostages, and for some peace and quiet across all of Israel.